Confirming the Altamirano Connection to Conquistador Fernando Cortés

- Steven Perez

- Apr 29, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: May 2, 2025

Damien Aragon’s research on the ancestry of Francisco Valdés Altamirano led to the extraordinary finding that he was descended from several conquistadors who served under Fernando Cortés when the Spanish army and its native allies conquered Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) in 1521 (“Going by the Book: Further Research into the Valdés Altamirano Family,” in the September 2022 edition of the New Mexico Genealogist)

In the June 2024 edition of the New Mexico Genealogist, Damien and I worked with Karen Bowman to update and expand the Altamirano side of the family tree in our article “Corrections to the Genealogy of Juana Altamirano, Paternal Grandmother of Francisco Valdés Altamirano.” This investigation showed that Francisco’s ancestor Juan Altamirano was Cortés’ first cousin. I recently found more evidence that confirms Petronila Altamirano was married to Juan Altamirano (Saavedra) and reveals new information about him.

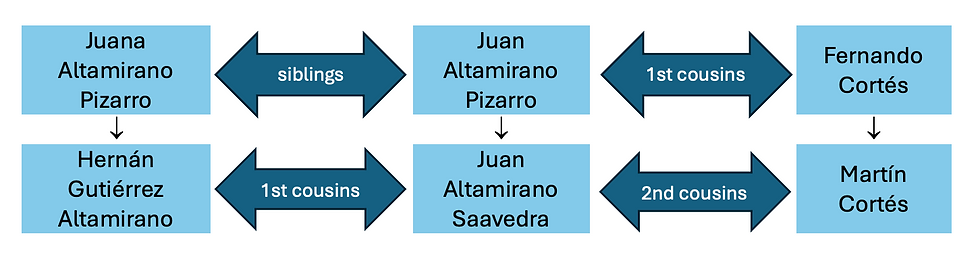

A manuscript from the year 1569 located in the Archivo General de la Nación (Mexico) describes a lawsuit between Petronila Altamirano and Hernán Gutiérrez Altamirano as executors of Juan Altamirano, deceased, and Don Martín Cortés, the Marquess of the Oaxaca Valley, who was Fernando Cortés’ first-born son and heir. Fernando was Juan’s first cousin and Don Martín was Juan’s second cousin, as shown in the diagram below.

In the lawsuit, the Altamiranos sued the Cortés estate for 348 pesos and 2 grains of gold for the salary owed to Juan Altamirano for a year and a month that he served as the alcalde mayor of the Villa of Coyoacán (Side note: anyone who has been to Mexico City knows that today Coyoacán is a trendy and bohemian neighborhood, home of the Frida Kahlo Museum).

The fact that Juan Altamirano Saavedra served as the alcalde mayor of Coyoacán, which was the encomienda assigned to Fernando Cortés, demonstrates just how close the two families were. Juan’s father Juan Altamirano Pizarro had served as the accountant for Cortés’ estate. The younger Juan had evidently maintained this relationship by being selected to govern the administrative seat of the Cortés family’s domains.

During the course of the lawsuit, we learn that Juan Altamirano Saavedra died on 20 March 1567 and that Petronila was the guardian and conservator of their children. Extrapolating from the baptism dates of their children and the fact that he was born in Mexico City, Juan would probably have been only about 37 years old when he died. Don Martín’s attorney argued that the money owed had already been paid, as demonstrated by a receipt of payment signed by Hernán Gutiérrez Altamirano. Hernán disputed this assertion and claimed that he had never received the payment.

“...de la dicha Doña Petronila Altamirano muger que fue de Juan Altamirano difunto como su albacea y tutora e curadora de sus hijos y del dicho difun- to y de Hernan Gutierrez Altamirano albacea...” | “...of the said Doña Petronila Altamirano, who was the wife of Juan Altamirano, deceased, as his executor and guardian and conservator of their children and the said deceased, and Hernan Gutierrez Altamirano executor...” |

The royal audiencia rendered its final judgment in the case on 25 October 1569, ordering Don Martín to make the full payment as requested by the Altamiranos. Doña Petronila’s assignee, Antonio Gómez, confirmed that he received payment from the royal officials on behalf of the Cortés estate on 3 January 1570.

Unfortunately the manuscript does not give any information about Petronila’s lineage, although it is likely, based on her last name, that she also had a family connection to Fernando Cortés. Any new information I find will be posted in a future update.

Subscribe to the blog to receive email updates.

The reference to "Spanish Army" in the introduction of the post albeit is conventional wisdom is at best misleading and deceptive at worst. Matthrew Restall in his Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest, cogently argues that term "soldier" incorrectly depicts the conquerors as the action arm of the king "granting the "Spanish royal state" to take a "monolithic and directives role in Spanish expansion" which Restall calls the "myth of the king's army." And so. how did they seem themselves Restalll asks. In the main, to "acquire wealth and status." To quote James Lockhart, "free agents, emigrants, settlers, unsalaried, and ununiformed earners of encomiendas and shares of treasure."

Moreover, Spanish army denotes large numbers of fighting men. The most fight…

Thank you for posting

Excellent find thanks for posting.