Antonio de Carvajal: Conquistador, Procurador and Regidor of México (Part 4 of 4)

- Steven Perez

- Aug 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 17, 2025

After Antonio de Carvajal's return to Mexico City, he continued serving as a procurador and was elected to one of the two alcalde ordinario positions on 1 January 1533. The second audiencia of New Spain began governing on 12 January 1531, introducing a number of reforms that the conquistadors resented and opposed. The city council wrote a letter to the king on 6 May 1534 with a long list of complaints, denouncing the “bad governance” of the second audiencia. The document was signed by Antonio de Carvajal and Bernardino Vásquez de Tapia. The grievances included the following:

Some encomiendas were revoked and indigenous towns placed under a new system of corregimientos. The council alleged that tribute had often been reassigned to new settlers who did not deserve such rewards—relatives and associates of the audiencia—leaving conquistadors in poverty. An exemplary line from the letter reads: “Most Powerful Lord, may Your Majesty provide, for it is only right that those who won the land should not suffer such lasting misery, given the need and expenses left over from the conquest, and that they are still not free from debt, and are dying of hunger, and some have even died from it.” Under these circumstances, the letter alleged that many of them saw no recourse but to return to Spain.

Taxes were introduced on the encomienda income, which was a hardship for both the natives and the Spaniards.

The founding of the new city of Puebla de los Ángeles siphoned labor away from the encomiendas. In addition, its location in the province of Tlaxcala was prejudicial to the native allies who had helped the Spaniards in the conquest. They suggested Michoacán as a more appropriate province for locating a new Spanish settlement.

The founding of the new city of Santa Fe near México City harmed the development of the capital and exposed the Spanish population to danger by spreading the population out across a greater geographic area.

The Franciscan priests often meddled in civil affairs and acted as if they were the sole authority in these lands. The Franciscans deprived the Spaniards of native labor, arguing that the Spaniards should live off the land as they did in Spain, where there were no encomiendas.

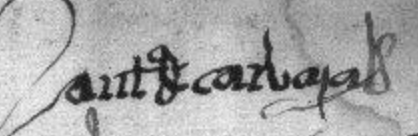

Signature of Antonio de Carvajal on letter from Mexico City Council to the king

6 May 1534

Archivo General de Indias, Patronato, 180, R. 53

In 1535, Carvajal became a permanent member of the city council (regidor perpetuo), a position of great importance and prestige. He was also designated as procurador mayor in 1537 and alférez real for the procession of banners during the feast of San Hipólito in 1541. By about 1545, Carvajal and his wife Catalina de Tapia had eight daughters and one son, some of marriageable age, as recorded in a manuscript chronicling all of those who took part in the conquest:

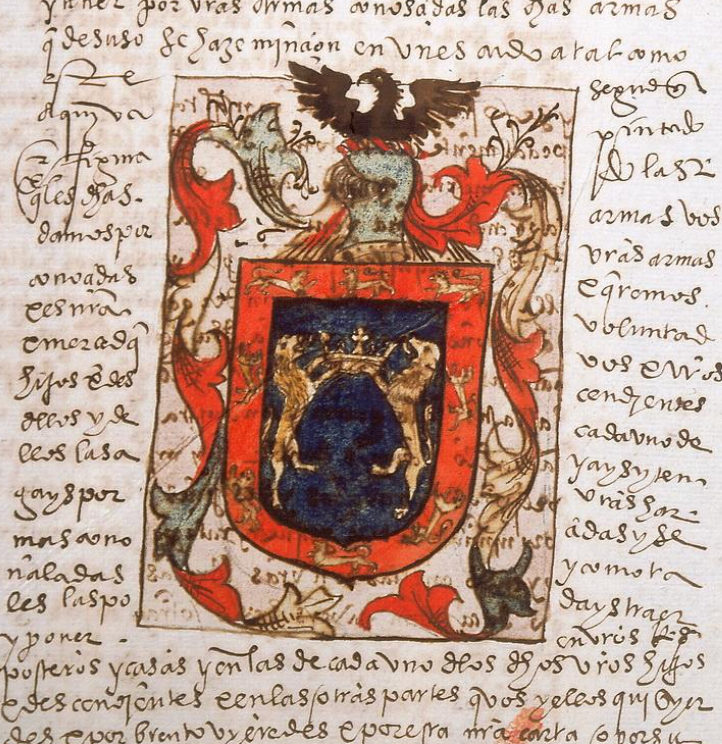

Relación de Antonio de Carvajal

Archivo General de Indias, Mexico, 1064, L. 1, fol. 30r

Antonio de Carvajal: He is a resident and council member (regidor) of this city of Mexico, and a native of the city of Zamora, and the legitimate son of Pedro González de Carvajal and Isabel Delgadillo; and it has been twenty-eight years since he came to these parts, and twenty-six years since he arrived in New Spain, together with a nephew of his, who died during the siege of this city; and he was one of the captains appointed for the brigantines, and he was present at the conquest and capture of this said city, and later at those of Pánuco and Tututepec and along the coast of the South Sea; and he served as visitor (visitador) of some provinces of this New Spain, and he destroyed idols and temples (cúes); and he was a procurador of this land to the kingdoms of Castille, from where he returned married; and he has eight daughters and one son, some of whom are of marriageable age; and he served as alcalde ordinario in this city, where he has his house, occupied with his arms, horses, and household; and he holds in encomienda the town of Zacatlán, for which he presents a tax assessment report.

By January 1552, Carvajal was feeling the weight of his years, for he presented a petition before the royal audiencia asking the king and Council of the Indies to allow his sixteen-year-old son, also named Antonio de Carvajal, to succeed him as regidor perpetuo of Mexico City once he passed away. At the time, he indicated that Antonio was his only son and that he also had nine daughters. He presented ten witnesses who could vouch for his loyal years of service to the Spanish Crown, including his old friend Gerónimo Ruiz de la Mota. Ruiz revealed in his testimony that Catalina de Tapia, legitimate wife of Carvajal and mother of all the aforementioned children, had passed away on Christmas Eve 1549. The other witnesses were Pedro de Solís, Gabriel de Aguilera, Gonzalo de Salazar (likely the son of the infamous factor who Carvajal had allied himself with years earlier), Diego de Villapadierna, Bartolomé Alguacil, Juan Cano, Francisco de Olmos, Diego de Escobedo and Juan de Zaragoza. It is unclear if there was any answer to this petition.

In 1559, Carvajal married Doña María de Olid y Viedma, daughter of the conquistador Cristóbal de Olid (the one who had led the mutiny in Honduras), but they never had any children. In April 1562, Carvajal formally renounced his position as regidor saying that he was too old and sick to serve in office and once again asked the king to allow his son to succeed him. He presented witnesses who could attest to his record of service and the suitability of his son, including the conquistadors Francisco de Montaño and Pedro Solís as well as Gonzalo de Salazar, Hernando de Herrera, Jorge Cerrón Carvajal (no known relation). His son then presented his own petition with additional witnesses—the conquistadors Diego Hernández Nieto and Alonso Ortiz de Zúñiga as well as Luis Ramírez de Vargas, Diego Agundez, and regidor Bernardino de Albornoz (probably the son of the infamous contador). On 1 January 1563, Carvajal attended a meeting of the city council for the last time and on January 18th a royal decree from Madrid acknowledged his resignation in favor of his son, who assumed office on 2 October 1564. On 5 June 1564, the elder Carvajal served as a witness for the conquistador Alonso de Ávila but was too crippled by gout to be able to sign his name.

If Carvajal had hoped that he had secured his son’s future, events would shortly prove otherwise. The grievances described by the city council in 1534 had continued to fester and the second generation of Spanish criollos (those born in New Spain) felt especially neglected by the monarchy. In the summer of 1566, a faction of the criollo elite—led by Don Martín Cortés, the Marqués del Valle—attempted to overthrow the government and install Cortés as king of New Spain. The authorities became aware of the plot, arrested Don Cortés and the other rebels, and executed the ringleaders. Don Cortés, because of his status, was eventually allowed to travel to Spain to defend himself before the Council of Indies.

As the investigation around the rebellion continued, on 6 November 1567, Carvajal’s son was named as a close confidant and co-conspirator of Don Cortés, arrested and imprisoned. On 18 December 1567, the elder Carvajal passed away while his son was still in prison. We know the precise date because royal officials were instructed to embargo all of the younger Carvajal’s property. When they learned of the death of the elder Carvajal, his property, including the annual tribute from the encomienda of Zacatlán, became subject to the embargo from the date of his father’s death. One wonders if the anguish the elder Carvajal must have felt at the possibility of the family losing its wealth and status was too much for him to bear. The younger Carvajal was unable to handle the settling of his father’s affairs from prison, so the task fell to the elder Carvajal’s son-in-law Leonel de Cervantes. It was a sad coda to a remarkable life.

A future blog post will describe in further detail the rebellion of Don Cortés and the criminal trial of the younger Antonio de Carvajal. Subscribe to the blog to receive email updates.

Here is the genealogy of the family (based on all sources listed in this blog series)

Generation I

Pedro González de Carvajal

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Isabel Delgadillo

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Generation II

A. Antonio de Carvajal

(b. about 1494, Zamora City, Zamora, Spain)

(m1. about 1531, Spain)

(m2. 1559, Mexico City)

(d. 18 December 1567, Mexico City)

(1) Catalina de Tapia

(b. unknown, Torralba, Toledo, Spain)

(d. 24 December 1549, Mexico City)

(2) María de Olid y Viedma (no children from this marriage)

(b. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Generation III

A(1)1. Bernardina de Tapia

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Rodrigo de Carvajal

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

A(1)2. Antonio de Carvajal

(b. about 1535, Mexico City)

(m. about 1563, Mexico City)

(d. 16 November 1582, Mexico City)

María de Sosa

(b. unknown)

(d. unknown)

A(1)3. María de Carvajal

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Leonel Gómez de Cervantes

(b. unknown)

(d. unknown)

A(1)4. Gerónima de Carvajal

(c. 6 February 1538, Mexico City)

(d. unknown)

A(1)5. Isabel de Carvajal Tapia

(c. 6 August 1539, Mexico City)

(d. unknown)

A(1)6. Catalina de Carvajal Tapia

(c. 24 August 1542, Mexico City)

(m. February 1569) *Her brother provided her dowry on 23 Feb 1569 in Zacatlán

(d. unknown)

Gonzalo Gómez de Cervantes

(b. about 1541, Mexico City)

(d. unknown)

A(1)7. Ana de Carvajal Tapia

(c.12 April 1543, Mexico City)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown but before 1575)

Antonio de Carvajal Ortega de Castro

(b. unknown)

(d. unknown)

A(1)8. Leonor de Carvajal

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Francisco Infante Samaniego

(b. unknown)

(d. unknown)

A(1)9. Francisca de Carvajal

(b. unknown)

(m. unknown)

(d. unknown)

Sources:

Guillermo Porras Muñoz, El gobierno de la ciudad de México en el siglo XVI, "Los alcaldes ordinarios," UNAM, 1982.

Catálogo de Protocolos del Archivo General de Notarias de la Ciuded de México, “Poder especial,” Notaría 1, Volumen 150, Ficha 608, fol. 1493-1494, 1575. Names Antonio de Carbajal Ortega de Castro as widower of Ana de Carvajal, and Gonzalo Gómez de Cervantes, Leonor de Carvajal and Francisca de Carvajal as heirs of Antonio de Carvajal.

Catálogo de Protocolos del Archivo General de Notarias de la Ciuded de México, “Traspaso,” Notaría 2, Volumen 2, Legajo 2, Ficha 155, fol. 677v, July 1569. Names Doña María de Olid as widow of Antonio de Carvajal el Viejo.

Manuscripts from the Portal de los Archivos Españoles

Archivo General de Indias

Ciudad de México: información sobre el mal gobierno

Patronato, 180, R. 53

Relación de personas que pasaron a Nueva España

Mexico, 1064, L. 1

Méritos,servicios: Juan Infante, Antonio Carvajal: Nueva España

Patronato,74, N. 2, R. 5

Confirmación de Oficio: Antonio de Carvajal

Mexico, 169, N. 49

Méritos y servicios: Miguel de Palma: México, Honduras, etc.

Patronato, 66A, N. 2, R. 2

Proceso contra Antonio de Carvajal: rebellion Nueva España

Patronato, 220, R. 1

Averiguacón sobre sublevados: rebelión de Nueva España

Patronato, 203, R.5

Thank you.