The Conspiracy of 1566 in New Spain (Part 1 of 5)

- Steven Perez

- Oct 29, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2025

The principal cause of the 1566 conspiracy in New Spain to rebel against the king was the introduction of the “New Laws” of 1542 which prohibited the inheritance of encomiendas. This threatened to dispossess the richest, most distinguished families of their principal source of wealth and income. Understandably, the first generation of Spanish criollos—the children of conquistadors and first settlers who had been born in the colonies—were aggrieved by the change and were determined to reverse it.

The plan for the uprising was audacious but not well formulated in terms of how it would be executed. However, the fact that it had been planned by the sons of some of the most elite and well-regarded families of the city exposed the tenuousness of Spain’s control over its colony and shocked the colonial authorities out of their complacence. The key conspirators were Don Martín Cortés, who had inherited the title of Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca from his father Fernando Cortés, his two half-brothers Luis and Martín Cortés, Alonso de Ávila Alvarado, and his brother Gil González de Ávila. The latter were sons of Gil González de Ávila y Benavides and Leonor de Alvarado. The elder González de Ávila had arrived in New Spain after the conquest in 1524 along with Francisco de Garay and had participated in the conquest of Pánuco and Honduras.

The conspiracy occurred during a delicate time in the governance of the colony, as the viceroy Luis de Velasco had recently passed away and had not yet been replaced. A visiting oidor from the Council of Indies had suspended a few of the oidores of the audiencia real, leaving only three in power. The uprising was scheduled to take place on the eve of 12 August 1566 to coincide with the annual celebration of the conquest of Mexico. One group of armed men would lock the doors of the city council when they were in session, another group would seize control of the arsenal, and a third would assassinate the oidores of the audiencia. They would also kill the brother and son of the late viceroy and other royal officials. Luis Cortés would then lead a squadron to the ports of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa to prevent any ships from spreading news about the rebellion. The brother of the marqués, Martín Cortés, was responsible for taking control of the mines of Zacatecas. Once they had control over these and other strategic cities, they would proclaim Don Martín Cortés as king of New Spain. Arrangements had also been made to send emissaries to the Holy See in Rome to ask for official recognition of the new monarchy from the pope and to England and France to negotiate strategic alliances in exchange for preferential trade agreements. Once the new regime was established, all land would be distributed in perpetuity to the encomenderos and their heirs.

Baltazar de Aguilar Cervantes, grandson of the conquistador Leonel de Cervantes and Leonor de Andrada (my 15x-great-grandparents), learned of the scheme and confided in his cousin Agustín de Villanueva Cervantes. Agustín encouraged him, for the sake of his honor and household property, to report it to the authorities, which he did. The oidores began to quietly investigate the matter, summoning other witnesses to testify about the plan, including two brothers who were involved in it, Baltazar and Pedro de Quesada.

Under questioning, on June 6th, Baltazar revealed that he and his brother had gone to the home of Alonso de Ávila and, along with several others, had discussed the plan for the rebellion. Alonso had tried to convince the Quesada brothers to join with them in the plot, invoking the names of other encomendero families that had allegedly pledged their support to the cause. Among those named were the younger Antonio de Carvajal, son of the conquistador of the same name.

The oidores, determined to gather more evidence, sent Agustín de Villanueva to the home of the marqués to cautiously solicit information about the plan for the rebellion (they felt the marqués would trust him as a member of the encomendero class). Fearing he was falling into a trap and might be killed, Agustín confessed and received communion before going to the home of the marqués. However, the ploy succeeded and he returned to report everything he learned about the plot to the oidores. Then on July 16th one of the lead conspirators, Alonso de Ávila Alvarado, made his statement before the oidores corroborating the plan.

The oidores decided they had enough evidence to arrest Don Martín Cortés and that same day summoned him to the audiencia on the pretext that official papers had just arrived on a ship from Spain with orders from the king. It was customary for all the royal officials to be present at a ceremony for the opening of the official orders from the king, so the invitation did not arouse the marqués’ suspicions. The oidores ensured that their most loyal men were on hand to secure the room and the entrances to the audiencia chamber. Upon arriving, the marqués took his customary seat.

One of the oidores arose and said, “My Lord, give me your sword.” Cortés complied and the oidor announced, “You are under arrest by His Majesty,” to which Cortés, by one account, responded, “Why?” The oidor responded, “You will be informed later.” In short order, his brothers Martín and Luis were also detained as well as the Ávila brothers.

In retrospect, there was probably very little likelihood that the rebellion would have been carried out successfully and did not present a real danger to the king’s colonial officials. But at that time, they had no way of gauging the scope of the conspiracy and immediately launched an investigation to identify and question all parties involved. The contemporary account by Juan Suárez de Peralta described this period as akin to a reign of terror in New Spain. The audiencia prioritized its investigation into the conspiracy above all other business, deposing hundreds of witnesses and arresting anyone who might have been involved, including priests. Everyone lived in fear of being named as a suspect and imprisoned. Extracting confessions through torture was a common practice of the time, and halberdiers were stationed to prevent anyone from passing through the streets near the casas reales (government offices) on account of the screams of men being tortured. Heavily armed soldiers were seen constantly patrolling the streets of the city, even entering the churches and monasteries, which they had never done before.

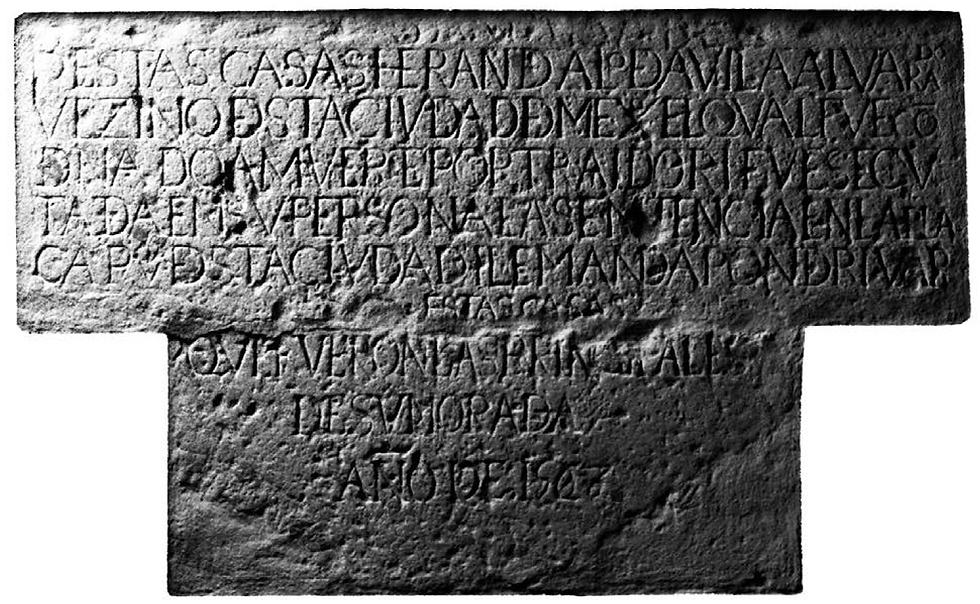

The first conspirators sentenced by the audiencia were Alonso de Ávila Alvarado and his brother Gil González de Ávila. Found guilty of conspiracy to rebel against His Majesty, they were sentenced to be publicly beheaded and to forfeit all of their property. Their houses were ordered razed and the plots sown with salt. A plaque was mounted in 1567 at the former location of their houses as a warning to others (see below).

Plaque commemorating the execution of Alonso de Ávila Alvarado. Currently located at Level IV of the archeological complex of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

From Boletín de Monumentos Históricos, Tercera época, núm. 41, p. 11

English translation of plaque: “These houses belonged to Alonso de Ávila Alvarado, a resident of this city of Mexico, who was sentenced to death as a traitor. The sentence was carried out in the plaza of this city, and they ordered these houses, which were his principal residence, to be demolished. Year 1567.”

Upon hearing the sentence in his prison cell, Alonso de Ávila hit the palm of his hand on his forehead, uttering, “Is this possible?”

“Yes, señor. It is best for you to make your peace with God and ask for his forgiveness for your sins.”

“There is no other remedy?”

“No.”

At which point, Alonso began to sob uncontrollably, tears running down his very handsome face. Only twenty-five years old at the time, he was known for his dashing appearance and was even jokingly referred to as a “lady” for how much effort he put into maintaining his physical appearance.

Alonso composed himself and lamented, “Ay, my children and my wife! Is this the honor that you had hoped to see? How much better would it have been for you to have been the children of a poor man who never knew anything about honor.”

According to Suárez de Peralta, the announcement of the sentence against the Ávila brothers caused great distress and confusion throughout the entire city because they were much loved, came from one of the most prominent and richest families, and had never done any harm to anyone. To dispossess them of everything—life, honor and property—seemed incredibly unjust.

On the day of his execution, 3 August 1566, Alonso denied the allegations again, saying that he had only intended to defend his own property in the event of unrest. He admitted to having spoken about this with Luis and Martín Cortés (brothers of the marqués), the marqués himself, Diego Arias de Sotelo, Baltazar de Aguilar, and Pedro and Baltazar de Quesada.

The Ávila brothers were carried by mules from the prison to a platform that had been erected in the Plaza Mayor. There, before throngs of spectators, Gil was the first to be beheaded. Upon seeing his brother decapitated, Alonso fell to his knees, rose one hand, and with the other twirled his mustache while intoning the penitential psalms. He very slowly untied the laces at his neck and looking toward his house, exclaimed, “Ay, my children and my dear wife, I am leaving you!”

At that moment, Friar Domingo de Salazar told him, “It is not time for that, señor. Instead, look to your soul as it is my hope in Our Lord that from here you will go directly to His glory. I promise to say a mass for you tomorrow, the day of my father Santo Domingo.” The friar then turned to the gathered crowd and said, “Señores, entrust to God these two gentlemen, who die justly.” Turning to Ávila, he asked, “Don’t you say as much?” To which Ávila replied, “Yes.” Sinking to his knees, he lowered the collar of his doublet and shirt. His eyes were tied with a blindfold and he bent to mutter a few words to the friar. They then placed him in position and the executioner struck him three times, each hit stirring up shouts of dismay from the crowd.

After the sentence was carried out, the heads of the Ávila brothers were nailed to the pillory for public display. Suárez de Peralta, passing by the plaza one day on his horse, was so overcome with grief that he wept more than ever before in his entire life, incredulous at what had happened.

The audiencia next commenced the trial of Don Martín Cortés, Marqués del Valle, relying on the statements of hundreds of witnesses already deposed—including the younger Antonio de Carvajal. His testimony is continued in Part 2.

Subscribe to the blog to receive email updates.

Sources:

Reiko Tateiwa Igarashi, “La Rebelión del Marqués del Valle: un Examen del Gobierno Virreinal en Nueva España en 1566,” Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie IV Historia Moderna, No. 29, Revista de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, 2016.

Isabel Arenas Frutos and Purificación Pérez Zarandieta, “El primero criollismo en la conspiración de Martín Cortés,” en Felipe II y el oficio de rey: la fragua de un imperio (Madrid: Ediciones Puertollano, 2001).

Juan Suárez de Peralta, Tratado del descubrimiento de las Yndias y su conquista, Transcription of manuscript from 1589 by Giorgio Perissinotto, (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1990).

Gabriela Sánchez Reyes, “El padrón de Alonso de Ávila Alvarado de 1567 y el templo

de Huitzilopochtli,” Boletín de Monumentos Históricos, Tercera época, núm. 41.

Archivo General de Indias

Proceso contra Antonio de Carvajal: rebelión Nueva España

Patronato, 220, R. 1

The history of New Spain like other histories of empires is one of elite families battling for political power, cleriics and merchants skirmishing for influence, and farming practices and boundary disputes inciting a constant source of conflict for large and smalln landowners.

What a horrific event!