The Forged Ramón Vigil (Pedro Sánchez) Land Grant (Part 2 of 2)

- Steven Perez

- Mar 21, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 28, 2025

Detection of Forged Grant Papers

The first time that questions were raised regarding the validity of the Ramón Vigil grant was during the September 1894 hearing before the Court of Private Land Claims regarding the Rito de los Frijoles grant. Since the Pedro Sánchez grant was referenced as the northern boundary of that grant, and had already been confirmed by Congress, the plaintiffs sought to introduce it as evidence that the Rito de Frijoles grant was similarly well-established. The plaintiffs’ attorney questioned Will M. Tipton, the custodian of the Spanish Archives of New Mexico, as to whether or not the signatures of the officials on the grant papers were genuine. Mr. Tipton testified that he believed all of the signatures on the grant paper were forgeries, specifically calling out those of Governor Gaspar Mendoza, Juan Joseph Lobato and Juan García de Mora. He also stated that he had never examined the Ramón Vigil grant papers.

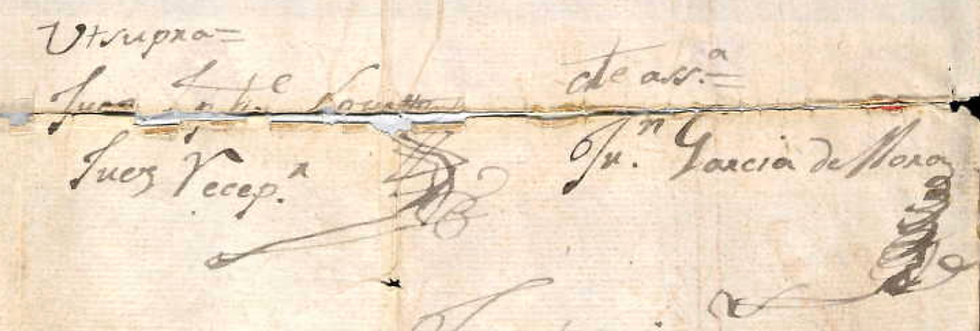

Genuine signature of Gaspar Domingo de Mendoza (left, from murder of Magdalena Baca case, Spanish Archives, Twitchell vol. 1 No. 437)

and forged signature from Pedro Sánchez grant (right)

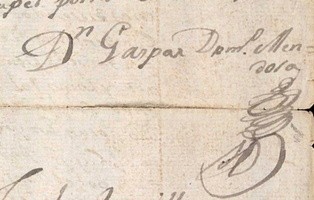

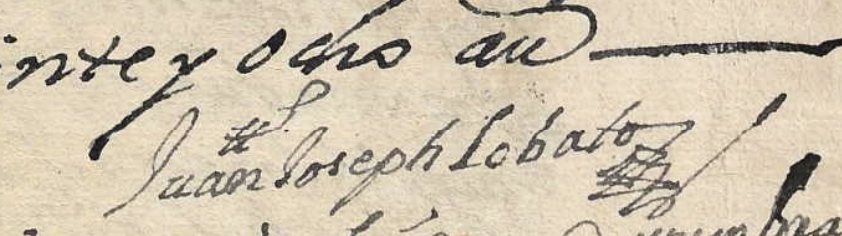

Genuine signatures of Juan Joseph Lobato and Juan García de Mora (above) with forged signatures from Pedro Sánchez grant (below)

Since this response was not helpful to the plaintiffs’ case, the attorney sought to discredit Mr. Tipton’s abilities as an expert witness. The US Attorney Matt Reynolds objected to the admission into evidence of the Ramón Vigil grant documents as they had come from private hands rather than the Spanish Archives, noting “if the surveyor general made a mistake in recommending it to Congress for confirmation, that is no reason why this court should confirm it.” However, there was no mechanism for protesting a grant that had already been confirmed by Congress and there is no record of any challenges to its validity.

The forgery was next detected by Marjorie Bell Chambers in 1974 in her PhD dissertation at UNM. She hypothesized that Pedro Sánchez had forged the grant papers. However, Malcolm Ebright in his book Land Grants and Lawsuits in Northern New Mexico explained that the Sánchez signature was also forged. He convincingly argues that what most likely happened was that the original grant papers contained a note indicating that the grant had been revoked in 1765. Therefore, Ramón Vigil forged new grant papers by creating a copy from the original, leaving out the note of revocation.[i] Although the original Pedro Sánchez grant had in fact existed prior to 1765 as described, Vigil’s forgery made it seem as if the grant was still valid.

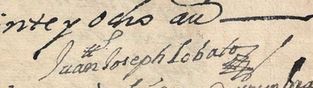

Genuine signature of Pedro Sánchez (left) and forged signature from grant papers (right)

Sale of the Grant and Subsequent Protests (1879-1908)

Just two years after the grant was surveyed, in 1879, Ramón Vigil sold the land to a Catholic priest, Thomas Aquinas Hayes, for $4,000. Within a month, Hayes sold the land to Edward Sorin of Indiana for $16,000. Hayes then bought the grant back from Sorin for the same price in July 1881.[ii] On July 8, 1882, Hayes filed a protest of the 1877 survey with the US Surveyor General Henry M. Atkinson. He pointed out that, according to custom, when mountain ranges were designated as boundaries, it was taken to mean that the grant included all the land up to the summit of the mountain. The original grant document had designated the Sierra Madre Mountains as its western boundary, but the survey had only measured from the foothills, thereby materially reducing the quantity of land granted. Hayes explained that he had been overseas at the time the survey was conducted and had not been informed, only becoming aware of it upon his return in 1881. This was a remarkable assertion, considering Hayes was not the owner of the grant at the time of the survey! He requested the surveyor general execute a new survey prior to the patenting of the grant.

To bolster his case, Hayes gathered evidence that the survey was not accurate. On July 25th, Atkinson took sworn depositions from several individuals regarding the grant’s boundaries. Hayes also submitted affidavits from a number of people with knowledge about the grant, including Ramón Vigil and his son José Francisco Vigil. The elder Vigil stated that neither he nor his neighbors had been notified about the survey and that the surveyors had not received proper instructions as to the grant’s boundaries. All the witnesses testified that the western boundary was the summit of the mountain, with some indicating the reason was that the top of the mountain offered better shelter and protection for the sheep and cattle during the winter, whereas the foothills were generally stony and barren.

Hayes also hired his own team of surveyors to verify the survey, receiving a field report from John Duval and Thomas Gwyn on September 16, 1882. Following the field notes from the 1877 survey, they had traced the steps of the original survey team, measuring distances as indicated, but were unable to find most of the landmarks indicated in the report. They noted “by reference to the notes contained in this report, you will perceive that the topography therein called for does not agree in any respect with the topography of the country described in field notes of the grant.” With this evidence that the survey had not been properly conducted, Hayes filed a report with the surveyor general, and a copy was transmitted to the US General Land Office.

On April 10, 1883, Commissioner Noah C. McFarland sent a response denying Hayes’ protest of the survey. Drawing upon precedents of similar cases in California, he argued that it had always been the practice of the US General Land Office when locating Mexican grants that where the mountain was the boundary, without more specific designation, the proximate foot or base was to determine the boundary line, as opposed to the summit. Although Hayes failed to have the grant enlarged, he still made an enormous profit when he sold it in July 1884 to Winfield Smith of Milwaukee and Edward Sheldon of Cleveland for $100,000.[iii]

Sometime after this sale, George W. Fletcher became a part owner of the grant. The new owners filed a protest with the US General Land Office, but it was dismissed on April 25, 1885. The land office contended that they had produced no new evidence and were presumably aware of the earlier decision regarding Hayes’ protest when they had purchased the grant. On May 11, 1885, Henry Atkinson (no longer the US Surveyor General, but as a private lawyer) submitted another protest to the US General Land Office on behalf of the owners. This time, they submitted affidavits showing that the 1877 survey had not properly measured the grant to the foot of the mountains, leaving out a portion of it. This protest was also denied, on the grounds that the 1883 decision had never been protested prior to the sale of the land to the new owners and that their new “allegations of fraud are altogether too vague and indefinite to make out even a prima facie case calling upon your office to institute the investigation asked for.” This decision was signed by the US Secretary of the Interior, Lucius Lamar on April 30, 1886.

When the grant was patented on April 9, 1908, it was signed for by B. Phillips. He may have been associated with the Ramón Land and Lumber Company, which had negotiated a contract with Smith and Fletcher to cut timber on the land and purchase the grant.[iv] Later, in 1911 and 1912, the US Surveyor General conducted restorative surveys to clarify the shared boundaries of the Baca Location No. 1, the Jemez Forest Preserve, and the Ramón Vigil Land Grant. Once accounting for these adjustments, the final area of the Ramón Vigil Grant was recorded as 31,209.52 acres.[v]

Note: the source of the information regarding the history of the grant can be found in the New Mexico State Archives, Land Grant Case Files, Survey General Report No. 38.

[i] Malcolm Ebright, Land Grants and Lawsuits in Northern New Mexico, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), p. 234

[ii] Ibid, p. 238

[iii] Ibid, p. 239

[iv] Marjorie Bell Chambers and Linda K. Aldrich, “A History of Los Alamos,” in Jemez Mountains Region, New Mexico Geological Society 47th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, available at: https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/downloads/47/47_p0101_p0106.pdf

[v] Thomas Merlan and Kurt F. Anschuetz, More than a scenic mountain landscape: Valles Caldera National Preserve land use history, (Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2007), p. 42, available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr196/rmrs_gtr196_031_047.pdf

Comments